A Year In Review: C.S. PhD Student Edition

As we approach the end of 2024, I want to reflect on my academic journey over the course of the year. I am around 2.5 years into my computer science PhD, which means I am either at the halfway point or close to it (in my department PhDs typically take ~5-7 years). My intended audience for this blog are fellow academics, anyone contemplating doing a PhD, and my mom (i.e., folks still learning what doing a PhD may entail). My goals in this post are:

- Describe the milestones I hit this year and the steps I followed to achieve them.

- Reflect on how my ability to process information and make decisions has evolved this year in the context of my day-to-day research workflow.

A few notable recent achievements: I defended my masters/passed my qualifying exam in April, spent the summer in Berkeley doing a research internship, supervised an undergraduate research project over the summer-winter months, and worked on some really cool research projects throughout the year.

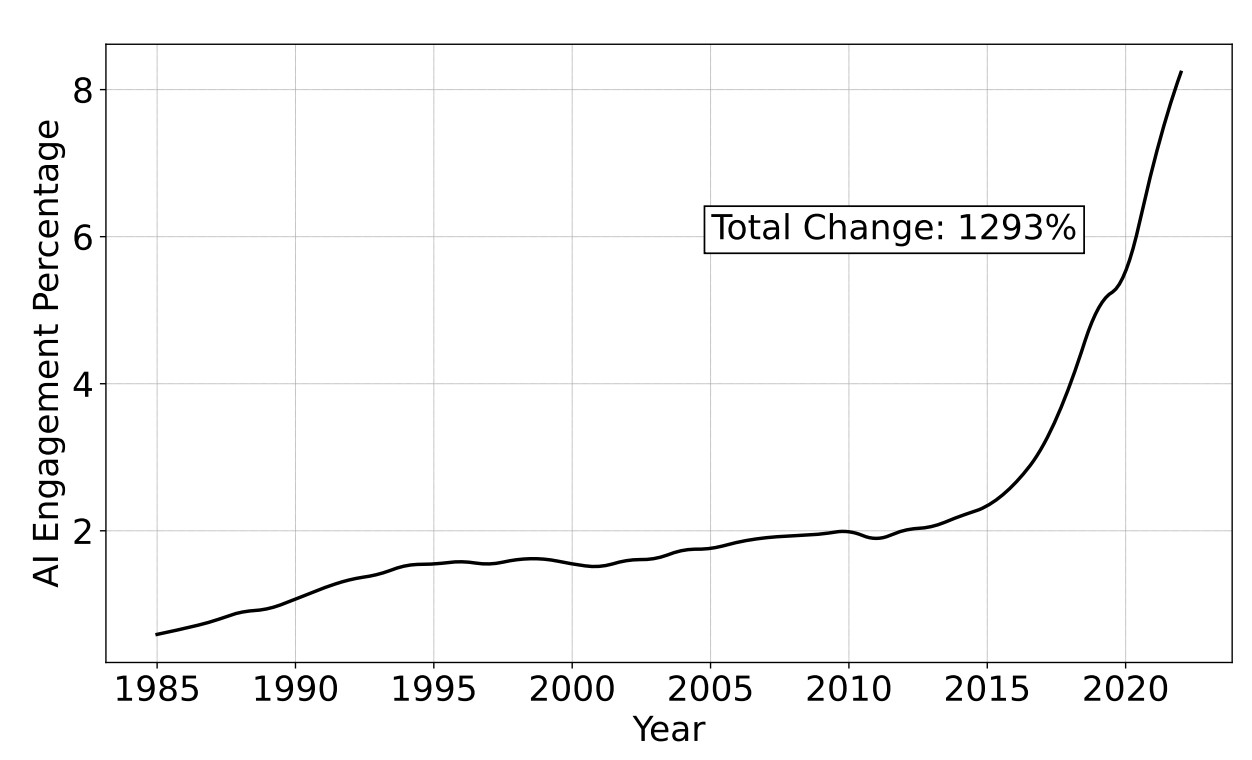

An interesting observation: The field that I broadly conduct research in for my PhD (machine learning/artificial intelligence) has been growing at an insanely fast pace [Duede et al., 2024]. As a graduate student, keeping up with all the research being produced and deciding what to act on is like drinking out of a fire hose.

Qualifier Exams

The qualification phase of the PhD in my department lasts roughly for the first 2-3 years and consists of both completing course requirements and conducting and presenting original research in the form of a mini thesis defense. My department also requires students to have a master’s degree to advance past the qualifier exam, so students who do not begin their PhD with a master’s must take additional courses to fulfill that requirement. This was the case for me, so I took extra courses and was concurrently awarded my master’s degree when I passed my qualifying exam.

The hardest part of the qualification phase of my PhD was selecting the research topic for my qualification thesis. My advisors were super supportive and flexible with me choosing to research anything I was interested in. The autonomy awarded to me is what attracted me to this group as I loved the idea of being my own boss. However, I quickly became overwhelmed when I started surveying the literature and realized how fast the area was moving. There were so many possible research topics…perhaps too many.

Looking back on this experience, I can see that I was paralyzed by the illusion of needing to make the perfect research topic choice all by myself. Turns out, there was no such thing as the “perfect” topic, as the field rapidly changed and so did my research question over the duration of my project. Also, I was never actually on my own. I had really amazing and useful brainstorming sessions with my labmates, very encouraging mentorship from postdocs, and gentle and structured guidance from my advisors who never lost sight of the big picture (even when I did). In the end, the topic I chose was suggested to me by one of my co-students (Aswathy Ajith), and the specific research questions I tackled were ironed out at my weekly research meetings. The hardest part was just getting started.

My research focused on better understanding how language models, like ChatGPT, reason (or fail to reason). I formed hypotheses, developed new methods to test my hypotheses, conducted experiments, and wrote up my results into my first workshop paper in Fall of 2023 [workshop paper]. This was the first research project I had ever led, and a challenging component of the project for me was clearly communicating my problem, motivation, methods, and results in my workshop paper. This is where my advisors really shined. I learned a lot about effective scientific writing by going back-and-forth with my advisors over my paper draft. I went on to present my first paper at the workshop to an audience of around 500 people (give or take 50 people – I remember doing napkin math in my head to estimate the number of people by counting the number of chairs as I walked on stage). It was my first academic talk to a wide audience and I was super nervous. I am told it went well. I remember very little of what I actually said.

In January 2024, I set out to expand my workshop paper into a full qualification exam thesis, which consisted of a much wider literature review of related work and more comprehensive experiments to answer a broader set of questions [qualifier thesis]. All of this work was done leading up to my qualifying exam: a public defense of my dissertation under the scrutiny of an academic committee. An academic committee is made up of both advisors and non-advisors, and their job is to read your thesis research, watch you present your research, and question you about your work to ensure that it is rigorous and merits advancement past the qualifying phase of your PhD.

My thesis writing and final set of experiments were more self-led than when I was working on the initial workshop paper (i.e., my advisors and postdocs did not give as much feedback). This led to self-doubt as I was not always sure if I was asking the right questions or if my arguments were sharp enough. Once again, I was facing decision paralysis. While it was important to make thoughtful choices, it was equally important to trust myself and just get started. What I was failing to remember is that a PhD is about building a body of one’s work, and hyper fixating on trivial aspects of any individual project can be counterproductive. Individual projects need to have clear goals, be founded on reasonable assumptions, and make evidence-based arguments. Once I remembered that, I was golden.

The actual oral defense for the qualification exam went well! I passed (and got my master’s degree) [video of rehearsal].

Summer Internship

The next big milestone of the year was spending summer 2024 in Berkeley working on my next research project. I did this as a part of an internship at Lawrence Berkeley National Labs; completing at least one internship was a requirement of my fellowship.

Like my qualification exam project, I had full autonomy over designing my internship project. I had the help of two supportive internship advisors (Michael Mohoney and Yaoqing Yang). I had decided I wanted to work on a project at the intersection of privacy and language modeling. Unfortunately, when I arrived in Berkeley, I very quickly realized that the specific idea I had in mind had actually already been done by a different group. I was left feeling as though I had failed the very simple task of scoping the project before I had even started. I tried brainstorming related problems, but nothing really spoke to me.

I wallowed for a few days, but luckily I was getting better at rolling with the punches, soliciting feedback, and adapting in the face of challenges after my qualification exam project. Eventually, I decided that a different idea that I had been playing around with prior to my internship might yield a fruitful direction. My internship advisors agreed.

My internship project ended up focusing on mitigating unwanted memorization in language models. Once I overcame my initial self-doubt, the three months whizzed past. I even made a pitstop in DC halfway through the summer to present my preliminary research at my fellowship’s annual review. By the end of the summer, I had surprised myself at how much I had accomplished. I was running the very last of my experiments (much larger scale experiments than my qualification project), and I had a very rough first draft of my paper done. In retrospect, I am astonished at how much faster my second project went than my first.

After my internship ended, I continued polishing up my internship paper at my homebase in Chicago. This time around, in addition to my two wonderful primary academic advisors, I was also being advised by my two awesome internship advisors. Like my first project, my advisors (both PhD and internship advisors) worked miracles on my writing. This was a super useful and, at times, tricky experience: all four advisors gave sage but often completely contradictory advice. On many occasions, I was left wondering which advice to take and how to combine various research philosophies as all four advisors had unique academic backgrounds.

At first, I tried to accommodate everyone’s ideas, but that led to a really non-cohesive second draft. I began to realize that I might need to make some executive decisions about high-level directioning on my own. I spent a lot of time worrying that I was going to burn bridges with one or more of the advisors based on whose edits I chose to keep and whose edits I discarded. Once again, decision paralysis struck.

Eventually, one of my postdocs told me to trust my gut and reject edits that I thought didn’t fit my vision. This was spot-on advice; as soon as I started critically evaluating feedback, my co-authors and advisors were able to tailor their advice to the organization/tone of writing I had set [internship project]. Looking back, I realized that research really is a collaborative process and the right team will help you fulfill your vision rather than bog you down.

Mentoring an Undergrad Student

The final milestone of my year was designing and advising a Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) project. I designed the project with a few labmates prior to the summer: an extension of my qualifier exam thesis research that focused on developing methods to isolate components of a language model that are responsible for “toxic” behavior (e.g., slurs, racism). When scoping this project we factored in: a three-month timeline for the undergrad student, the skills the undergraduate student had listed on their application to the REU program, and the student’s future goals (applying to PhD programs in fall 2024).

There were a lot of unknowns during project scoping (e.g., Did the student find the project interesting? Would we get scooped? Would our methods work?). However, unlike when I scoped projects for myself, I didn’t have any decision paralysis. I was confident that we would be able to anticipate or react to any challenges or setbacks my student faced over the course of the summer.

Interestingly, my REU student and I did not physically overlap in Chicago since I was in Berkeley for the summer. Instead, I co-supervised my student remotely with a postdoc and team of fellow PhD students who were still at UChicago over the summer. My student did an awesome job, and we helped him submit his work as an extended abstract to two workshops – both of which were accepted [extended abstract].

I met my student in person when he presented his summer work at a poster competition at one of the workshops in November 2024. He did a great job – such a great job in fact that he proceeded to the final round in the poster competition. We found out the night before the final round that our student had qualified and that he would need to have prepared a 10 minute presentation for the next day.

The next morning was a mad dash with me on the ground helping my student prep his verbal presentation while a postdoc (Nathaniel Hudson) helped edit the slides remotely. I could tell that my student was really nervous. I suspected his nerves may, in part, be due to the information overload on best-presentation-practices that myself and the postdoc were throwing at him. I realized that I had been in his position countless times: having a lot of information available to me and not knowing which pieces to act on. I ended up telling the student the thing that helped me most: you have to trust your gut and just discard advice that is not useful to you. In the end, my student crushed it! His talk was authentic and I saw which pieces of advice he chose to keep. He won 1st place in the competition!

Final Reflections

I have loved being a PhD student. Working in a fast-moving field has been both rewarding and challenging as I am constantly sorting through information and trying to decide the best course of action. Working with large teams has been exciting because I learn so much, but reconciling tons of different opinions was daunting at first. Mentoring students has been super fulfilling but came with the challenge of anticipating my student’s needs and advising in a way that is constructive and not overwhelming. I learned a lot this year, and most importantly I grew more confident in both my decision making and problem solving abilities in the face of limitless information and possibilities.

Thanks to Jay Sakarvadia, Sahil Sethi, Jordan Pettyjohn and Valerie Hayot-Sasson, who provided feedback on this blog post.

References

[Duede et al., 2024] Duede, Eamon, et al. “Oil & water? diffusion of ai within and across scientific fields.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.15828 (2024).

[workshop paper] Sakarvadia, Mansi, et al. “Memory Injections: Correcting Multi-Hop Reasoning Failures during Inference in Transformer-Based Language Models.” The 6th BlackboxNLP Workshop.

[qualifier thesis] Sakarvadia, Mansi. Towards Interpreting Language Models: A Case Study in Multi-Hop Reasoning. 2024. University of Chicago, Master’s Thesis.

[video of rehearsal] “Interpreting Language Models: Correcting Multi-hop Reasoning Failures During Inference.” YouTube, uploaded by Mansi Sakarvadia, 7 Apr. 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4EE9DIToERo.

[internship project] Sakarvadia, Mansi, et al. “Mitigating Memorization In Language Models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.02159 (2024).

[extended abstract] Pettyjohn, Jordan Nikolai, et al. “Mind Your Manners: Detoxifying Language Models via Attention Head Intervention.” The 7th BlackboxNLP Workshop.